Günther Prien

Morale is restored

Over the Summer of 1940, Dönitz retained his firm belief in his crews, working overtime to restore morale and confidence while at the same time making strenuous efforts to resolve the problems with the torpedoes. The sensitive and complicated magnetic pistol was replaced with a pistol that fired on impact, though even this did not offer an immediate end to the problems.

The respect that the U-boat crews had for their Commander in Chief was to prove decisive, as they gamely steeled their nerves and set out again in spite of the continuing torpedo issues. That many of them managed to overcome these difficulties was testament to both their skill and resolve; Günther Prien proved to be a shining example, and was not found wanting. Over the course of the summer and early autumn, his fortunes were to change dramatically.

The Summer of 1940: The "Happy Time"

The Summer of 1940 was to see great successes for the German armed forces - France was swiftly conquered, and Britain was on its knees, awaiting the imminent invasion. This period was also to see what was called the "Happy Time" for the U-boat crews, with the Wolfpacks wreaking havoc among lightly-defended Allied shipping. Prien quickly forgot his disastrous fifth patrol in Norway, and put out from Kiel on 3 June hoping for better fortune. All seemed to start well when on 6 June, three days into the patrol, U-47 successfully rescued three Luftwaffe bomber crewmen whose aircraft had been shot down over the Atlantic; having been welcomed on board it must have been some experience for the airmen, who had to spend a month in unfamiliar conditions sharing the latrine with forty other men and eating nutritious submarine food!

The period following the rescue of the airmen saw Prien and his crew play the familiar old waiting game; more than a week passed with not a single enemy vessel in sight. Early on the morning of 14 June, the waiting was at an end as U-47 encountered an juicy target heading towards him - Convoy HX-48: forty-two vessels, in seven lines of six. It was not such an easy target though: in addition to the fast escort vessels, enemy aircraft continually buzzed overhead. Prien's attempt to stay out of sight while trying to maintain the chase was doomed to failure, as the poor speed of the Type VIIB while submerged allowed the convoy to inch away out of range. Every time he attempted to deliver an attack, there was something their to thwart him. After a fruitless three-hour chase the convoy could still be seen on the horizon, but following an emergency crash-dive to avoid a marauding Sunderland it had all but disappeared from view. All was not lost however, for at long last a tangible target appeared in the form of the British steamer Balmoral Wood, which had fallen away from the main convoy. One eel was launched, followed by a resounding explosion minutes later. Not long afterwards, the freighter had found its way to the bottom, leaving on the surface a sorry trail of debris - aircraft parts, wings and fuselages that had broken out of the crates that had contained them.

The sinking of the Balmoral Wood was to prove to be the first of a long list of victims in what was to be a highly successful outling; in stark contrast to the earlier fiasco in Norway this sixth patrol was to be Prien's longest and most successful in terms of both ships sunk and tonnage recorded, measuring in at a staggering 51,189 tons. In a particularly hot period between 21 and 30 June, U-47 accounted for six further enemy vessels - the British freighters San Fernando and Empire Toucan, the Panama-registered steamer Catherine, the Norwegian freighter M/S Lenda, the Dutch tanker Leticia, and the Greek freighter Georgios Kyriakides. During the attack on the San Fernando Prien made a series of uncharacteristic miscalculations that were to dramatically reduce his final tonnage estimation: in addition to underestimating the tonnage of the San Fernando itself (he calculated it to be the 12,100-ton Cadillac) he also thought that two more torpedoes had been successful in taking down another 7,000-ton freighter and the 5,600-ton Gracia. One can only assume that these miscalculations were driven by the spirit of competition that had started to develop between Prien and his former 1. WO Engelbert Endrass, now commander of U-46.

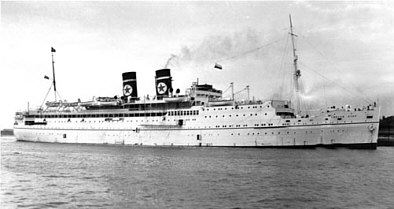

U-47's most significant victim on this patrol however was its eighth and final one, the British tranport Arandora Star, which before the war had been a well-known and popular cruise liner. Unbeknownst to Prien, the Arandora Star had on board over eighteen hundred people, the majority of whom were German and Italian prisoners, among them a number of civilian internees, on their way to the internment camps in Canada. Despite its cargo, there was nothing on the vessel that indicated its purpose; Prien therefore acted as he would have done with any other enemy vessel. Just after an hour after the single-torpedo attack on 2 July, the ship quickly sank in dramatic fashion, taking with her 805 lives, over seven hundred of which were Germans and Italians.

Left: The steam freighter and pre-war luxury cruise liner "Arandora Star", sunk by U-47 on 2 July 1940 en route from Liverpool to St. John's in Newfoundland. Unknown to Prien, the unescorted liner had been carrying a number of German and Italian POWs and internees. Right: Members of U-47's crew with the tonnage pennant representing the Arandora Star - 15,501grt.

The losses aboard the Arandora Star would have been far worse had other British vessels not arrived on the scene to pick up the stricken survivors. With the high command unaware of the loss of life, Prien was once more singled out for praise following his return to port on 6 July; nevertheless, given the fact that the Arandora Star was both armed and unmarked, he could hardly be blamed for his actions. There was another twist to the story of the sinking of the Arandora Star; according to Prien's wartime biographer Wolfgang Frank, the torpedo that accounted for the liner had been written off as a no-hoper and was fired only after Prien, attempting to top Endrass whose U-46 had returned to port having accounted for over 54,000 tons of enemy shipping, had persuaded his torpedo engineer Peter Thewes to tinker with the faulty eel. Such was fate: having seen ten torpedoes misfire in Norway, it was a dud that sent the Arandora Star to its doom. Frank summed up the contradiction succintly:

A whole book could be written about torpedoes. No weapon is so contrary. There are those which "must do the trick" and fail, others which have a right to misfire send 15,000 tons to the bottom.

(Wolfgang Frank, Enemy Submarine)

U-47 finally returned to port on 6 July, claiming a figure of 66,587 tons which was proudly emblazoned on both sides of the conning tower for all to see as the vessel rolled into port. The ten tonnage pennant flags fluttered equally proudly from the attack periscope. While the conning tower indicated a total of 66,587 tons, the total sum of all the figures on the ten pennant flags was 66,597 - which meant that either one of the pennants was wrong or there was a poor mathematician among the crew! Although the figures would be dramatically revised and taken back down to a totoal of 51,189 tons, Prien had achieved his goal in topping the figure posted by the "young pup" Endrass, whose final confirmed figure was calculated at 44,129.

Left: An ecstatic Günther Prien standing on U-47's conning tower at the end of his sixth and most successful patrol. Note the tonnage pennants and the figure of 66,578 representing the estimated total tonnage. Right: Prien chatting with the Luftwaffe bomber crew who were rescued from the Atlantic on 6 June. (Thanks to Ivan for this image)

After spending the best part of two months undergoing rest and refit, U-47 put out to sea for its seventh patrol at the end of August, and was to play a significant part in what was yet another killing spree for the U-boat fleet. Over the course of this thirty-one day patrol, Prien's boat dispatched seven enemy vessels for 34,973 tons, beginning with the unescorted Belgian cargo transport Ville de Mons sunk by torpedo on 2 September and the British steamer Titan, which was sent to the bottom two days later.

This was simply the prelude to what was to be a successful period for Prien, who made his way to the slow convoy SC-2 by 6 September, alongside the U-65 commanded by Kapitänleutlant Hans-Gerrit von Stockhausen. Early on the morning of the 7th, Prien launched his attack, striking three vessels - the British freighters Neptunian and José de Larrinaga and the Norwegian steamer D/S Gro - in just under one and a half hours. This burst was followed by the sinking of the Greek freighter Possidon two days later.

After its success against convoy SC-2, U-47 - which had only a single torpedo remaining - was assigned as weather boat, a mundane but essential task. On 20 September, it sighted the forty-ship convoy HX-72, and quickly called in a team of eight other boats. Its job done, U-47 was ordered back to port. Not to be outdone however, Prien joined in the attack, using his last torpedo against the British freighter Elmbank before turning the 88mm deck gun on the stricken vessel, which was eventually finished off by one of the other famous U-boats, U-99 - commanded by Kapitänleutnant Otto Kretschmer.

U-47 returned to dock at the French base of Lorient on 25 September after yet another highly productive mission. The one blot had been the tragic loss of a crewman, Matrosen-Stabsobergefreiter Heinrich Mantyk, who had been swept overboard while manning the deck gun on 5th September.